By Vanessa Pius, President’s Office Intern

The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. highlights landmarks in American air travel, military aeronautics, space exploration and some of the pioneers who made those milestones possible. Among the planes, diagrams, and tangibles in this family-friendly museum, there are two walls dedicated to women at the museum: one about the (sexist and racist) requirements for flight attendants in the 1950’s, complete with a full length mirror to see if visitors measure up, next to part of a plane from the same era that visitors can walk through to check out the cockpit. Another wall stands inside the hall for early aviation, decorated with pink paint, photos, and short descriptions of female aviators of the early 20th century. Woefully neglected are the female engineers and scientists whose invaluable contributions made so much of what visitors can see in the museum possible. One such woman was Margaret Hamilton, who worked on every manned Apollo mission, and several unmanned ones.

Before NASA selected their first class of female astronauts in 1979, Hamilton was working hard at MIT to make the Apollo missions possible. In 1960 when she was just 24 years old, Hamilton got a job as a programmer at MIT to support her husband while he was attending Harvard Law School. Her plan was to pursue a graduate degree in mathematics once her husband had earned his law degree (she had a bachelor’s in math and philosophy from Earlham College) but before long Hamilton was caught up in the lab at MIT and working on the Apollo space program.

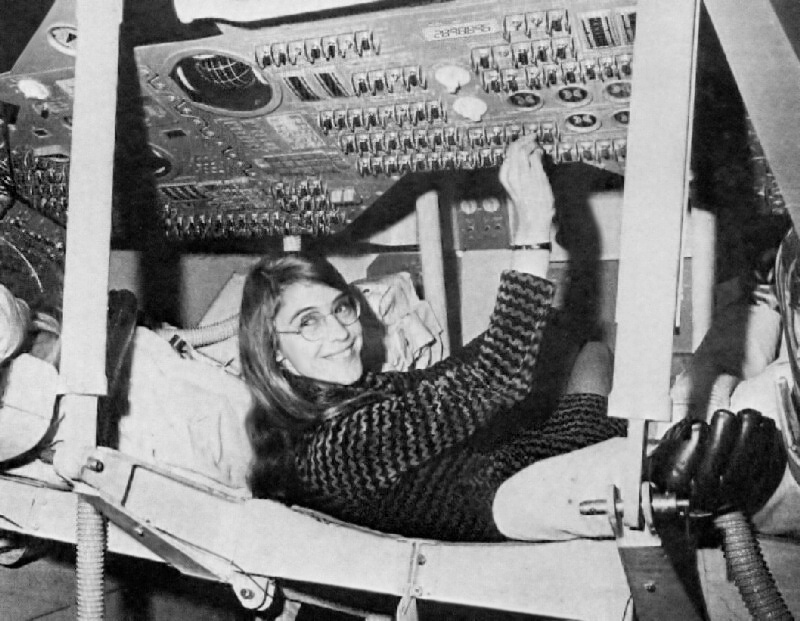

Not long ago, this photo of Hamilton standing next to stacks of critical coding surfaced on social media.

The black and white photo is unlike most photos of women from the era, and it’s clear that Hamilton is taking ownership of her work that made the Apollo 8 mission possible. Hamilton though, was unusual in more ways than one; not only was she a pioneer for science and women in STEM at a time when women were still encouraged to stay at home or take on more domestically appropriate occupations, but also Hamilton was a working mother. In fact, she took her young daughter, Lauren, with her to the labs at MIT in the evenings and on the weekends. Lauren was actually the inspiration for a crucial piece of coding in one of the manned Apollo missions:

One day, Lauren was playing with the MIT command module simulators display-and-keyboard unit, nicknamed the DSKY (dis-key). As she toyed with the keyboard, an error message popped up. Lauren had crashed the simulator by somehow launching a prelaunch program called P01 while the simulator was in midflight. There was no reason an astronaut would ever do this, but nonetheless, Hamilton wanted to add code to prevent the crash. That idea was overruled by NASA. “We had been told many times that astronauts would not make any mistakes,” she says. “They were trained to be perfect.” So instead, Hamilton created a program note—an add-on to the program’s documentation that would be available to NASA engineers and the astronauts: “Do not select P01 during flight,” it said. Hamilton wanted to add error-checking code to the Apollo system that would prevent this from messing up the systems. But that seemed excessive to her higher-ups. “Everyone said, ‘That would never happen,’” Hamilton remembers.

(Robert McMillan)

Hamilton programmed error-checking codes that allowed the Apollo 8 flight to successfully return to Earth, even when an astronaut aboard inadvertently deleted all the navigation data he had been collecting.

Hamilton would go on to found her own company in 1986, Hamilton Technologies. In an interview with medium.com, Hamilton said she founded the company “to accelerate the evolution of our technology and to introduce it to more users,” and continues to work to evolve technology for companies like Boeing, Hewlett Packard, Honewell, IBM, Motorola, and the US Navy.

While STEM fields remain diversity-challenged, especially in regard to gender, let Hamilton be an inspiration for more young women to enter STEM fields – until the Air and Space Museum has no choice but to include them.

Thank you for this! As a feminist woman in science I am alwys interested in pioneers and hadn’t heard of her at all before.

Surely they can find room for her in the museum displays!

YES! We need to honor Lauren Hamilton for sure. Each feminist’s story evolves us, the country, the world. And wow, do we do need to evolve humanity…

Her story reminds me of the artist Judy Chicago who created the The Dinner Party in 1979, considered the first epic feminist artwork. What it took for Chicago to fund, research, design, and find a permanent home for her installation that was record breaking for viewers around the world is epic.

Lovely article. Thank you for helping me learn more about Margaret Hamilton, a true woman pioneer.

Oh Arlene, I was transformed by The Dinner Party, viewed in Toledo Ohio museum. Still recall how the lighting and black surroundings truly carried it off.

And of course, this egregious example of a cultural gender bias vis a vis a Smithsonian Museum has to be confronted. Ignorance (of the Margaret and Lauren Hamiltons) is not bliss, it’s sexism plain and simple. Good story, well constructed